Table of Contents

A strong and durable touring frame can be constructed out of aluminium, steel or titanium. Frame material is just one factor of the overall frame design; what matters most is that the frame is engineered for the demands of touring, is constructed without imperfection and is offered by a manufacturer with a long history of building strong and reliable touring bikes.

Let’s dive into it!

Frame Materials: Which is Most Comfortable?

Road Vibrations and Bumps

Has anyone ever told you that steel and titanium touring bikes are comfortable and that aluminium frames result in a rough ride?

Believe it or not, bike frames actually account for very little of the overall vibration damping on a touring bike, especially when it’s loaded with bags. Road vibrations are mostly absorbed through your tyres, seatpost and saddle.

Think about it. Your tyre encounters a bump in the road, deforming and dissipating huge amounts of shock – a few millimetres on a narrow tyre right through to centimetres on a wide touring tyre. Your rim, spokes and hub are next, but their effect on the shock is minimal. Your hub transfers the remaining shock through the frame seatstay and up the seatpost where another significant effect on shock occurs – up to 25mm on some carbon posts. Lastly, your saddle will absorb a bunch more shock.

So perhaps a few millimetres of vertical flex separates some aluminium, steel or titanium frames, but it’s minimal when you consider all of the components that damp shock.

All frame materials will tour comfortably with good tyres, a seatpost designed to flex and with a cushioned saddle.

Resonance

All bikes have resonant frequencies at which they vibrate; in fact, everything you see around you is vibrating at one frequency or another. It is said that resonance can affect the comfort of your bike, but for the most part, components such as your tyres, grips, seatpost and seat will damp the majority of road vibrations.

Resonance can be a problem when it builds up so much that you develop ‘speed wobbles’ while riding at certain speeds. Bikes that ‘speed wobble’ also tend to lack stiffness.

Luckily most dedicated touring bikes are already built stiff enough to handle heavy loads, so this isn’t often a problem (unless you have heavy front panniers).

Sizing and Parts

Comfort isn’t just about vertical stiffness. Getting a frame that is your size and that suits your riding style will make a significant impact on how comfortable your bike feels to you. Finding a comfortable seat, seatpost and grips will go a long way too.

Which Is The Stiffest?

Any frame material can be used to build a stiff bike.

Frame manufacturers essentially make trade-offs by selecting different tube diameters and wall thicknesses, allowing a frame to be made stiffer, or stronger, or lighter. Touring frames are perhaps the stiffest of all frame varieties (and also the heaviest!) because they carry heavy loads on the front and rear, requiring a stiff enough chassis to reduce twisting.

Frame stiffness is often the first thing I take note of when I test ride different touring bikes. It’s one of the most important characteristics of a touring bike with front and rear panniers because it improves handling at high speeds and prevents speed wobbles.

Which Is The Lightest?

The goal of any good frame manufacturer is to put frame material only where it’s needed. Aluminium and titanium are known for being lighter than steel – but is this true?

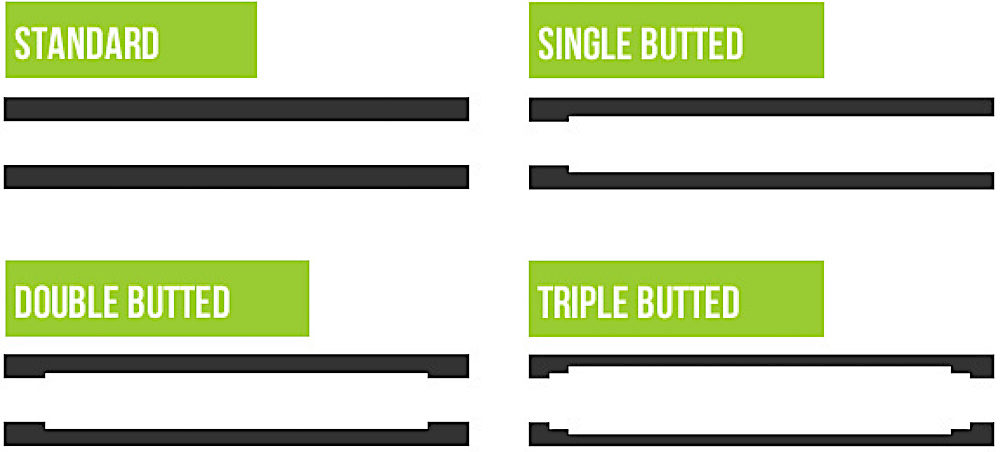

A process called ‘butting’ is designed to reinforce the joints at the end of frame tubes, making frames more robust. By taking material from the inside of a tube, it can be optimised for stiffness and strength, and the side effect is a lighter frame.

Good frame manufacturers will use different tubing thicknesses, diameters and butting tapers across their size spectrum, optimising their tube characteristics for touring (ie. stiff and strong).

A titanium frame that is equal in strength to a steel frame is about half the weight and half the stiffness. To increase the frame stiffness to an adequate amount, titanium manufacturers use large-diameter tubing. This results in a frame that is strong and stiff, yet often lighter (and more expensive) than steel.

An aluminium frame is about a third as stiff, a third of the weight and half as strong as a steel frame with the same tubing specifications. You’ll notice that like titanium frames, aluminium frames also require large tubing diameters with thicker walls in order to maintain adequate strength and stiffness. Despite using more metal, bike frames made out of aluminium tend to be lighter than both titanium and steel.

Which Is The Easiest To Repair and Modify?

Getting it fixed

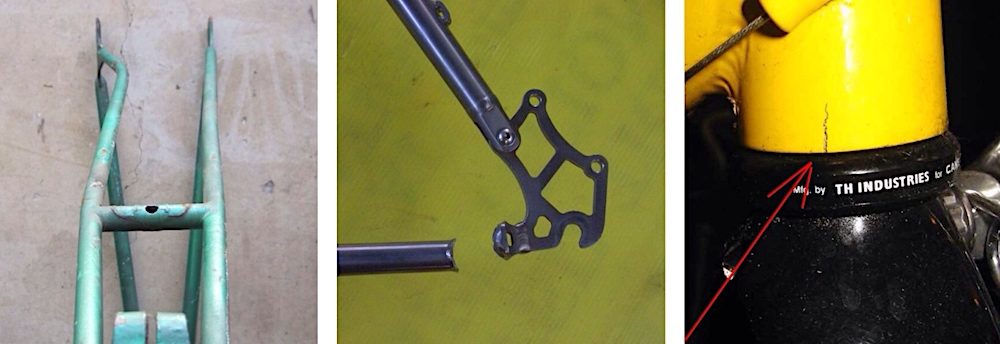

All frames are repairable. Steel is the easiest to repair, but don’t expect your roadside repair in Kyrgyzstan to be a permanent fix. Steel tubing is very thin compared to most industrial products and unless the welder makes bike frames for a living, there’s a good chance your frame will end up damaged in the welding process (although the quick fix may well keep you going).

Aluminium and titanium frames are repairable too; they, however, require more sophisticated tooling and expertise.

For a repair on any frame, a ‘weld up’ over the top of a crack is usually not enough. To make the weld strong, new material is required in the form of a gusset or sleeve.

Modification

Professional frame builders can modify steel frames relatively easily – just about anything can be replaced or redone. You can attach bidon mounts and disc brake tabs; you can even replace individual frame tubes, head tubes and re-space the rear dropouts.

Which Will Last The Longest?

Strength comes mostly from the engineering and build quality of a frame, rather than the material it is built with. A high-quality frame is very unlikely to break on a bike tour unless it goes through a traumatic experience such as a big front-end crash.

Fatigue

Steel and titanium frames have a ‘fatigue limit’ below which a repeated load (frame flex) can be applied an infinite amount of times without causing failure. Aluminium, on the other hand, has no fatigue limit, meaning that it will eventually fail after enough load cycles.

Although the lack of fatigue strength in aluminium frames seems alarming, they are engineered to be three or more times stronger than a steel frame, easily withstanding the stresses of bicycle touring. In short, a well-designed frame of any material won’t be affected by fatigue.

Defect Tolerance

After developing a defect, some materials separate quicker than others. Steel and titanium frames tend to bend and dent rather than shattering or snapping, providing you with a bit more warning between when you first notice a crack to when it ultimately fails. On the other hand, aluminium frames tend to develop cracks quickly and give way with a lot less warning.

Bolt Threads

Aluminium bolt threads are softer than steel threads. This can sometimes result in stripped out threads if you aren’t careful. Make sure to use a little grease on your bolts and pay attention to your bolt going in straight.

Rust

Steel is vulnerable to rust, but it is rare that a bike frame will actually fail for this reason. Just check out how many 30 to 50-year-old steel frames still get around despite living outside.

The reason rust isn’t a huge problem is that steel tubes are relatively thick, and are coated with paint. You should apply anti-rust sprays inside your frame periodically, especially if you spend time in wetter climates or near the ocean. It’s also a good idea to touch up the paint on your steel frame from time to time too.

Summary

Aluminium, titanium or steel, you’ll want to choose a frame that has been designed specifically for the stresses of touring.

Manufacturers with a long history of engineering well-designed, bombproof touring bikes will ensure your frame will essentially last as long as you own it.

Brands like Santos and KOGA do wonderful things with aluminium. Co-Motion and Surly are well-known for their steel. Idworx knows their stuff when it comes to titanium touring bikes.

For a more technical read on this stuff (terminology galore!), head over to SheldonBrown.

🙂 Good said !

Great call! I tossed and turned before getting an aluminium Trek 920 after years on steel. Six weeks in to my NZ tour, its eating up occasional 130km+ days loaded on bitumen. I love that engineered airplane flex I can feel when it’s heavy. With the panniers off at camp setups its light and fun. And it loves the gravel and track. Even more so now with Salsa cowbells, the difference in the feel through the bars compared to stock is worthile. So glad not to have been put off this great bike by material.

Glad you’re liking the 920! They’re an awesome ride.

Alee, i would love to hear your opinion on my touring Bike, which is actually a MTB Trek 4100 ladies frame(the one with low top Tube). This Alu Frame profile is perfect to get on and off multiple times from the Bike on the way; very useful in case of accident since the Legs are no prone to get stuck on the fly (unfortunately i tried already with a similar Bike), and no more hits on the Arch of Triumph. Its has four panniers and a handlebar bag , rhyno lite Rims and Mondial tires, new coil ncx fork. The fat Alu tubes suggest to be a strong Bike but i expect to ride 20,000km on a variety of surfaces, i mean if this Lady Frame brakes down on the way i can strip it off, buy a normal MTB and replace all components. Do you see a likely Frame failure? (regards and great web-site)

Frame failures are few and far between. If you like the Trek 4100, I say ride it! Like you said, if it breaks it really won’t be hard to install the parts onto a new MTB frame. All the best.