Table of Contents

- What Is The Evil Chamois Hagar?

- Long Reach, Short Stems

- Front and Rear Weight Distribution

- Weight Distribution and Bikepacking Bags

- Advantages Of A Long Front Centre

- The Endo Angle

- The Looping Angle

- Chainstay Lengths

- Steering Speed

- Wheel Flop

- Progressive Geometry Summary: Evil Chamois Hagar

- How Could We Improve The Frame Geometry?

- Want An Evil Chamois Hagar For 25% of the Cost?

- What’s Next?

The Evil Chamois Hagar is a carbon gravel bike that is currently sparking lots of discussions thanks to its unusually slack headtube angle, long and low top tube, ultra-short stem and front wheel that sits well in front of the rider.

I happen to know a thing or two about frame geometry, so in this masterclass, we’ll be using science to determine whether “progressive” frame geometries make any sense on gravel bikes. I’ll be introducing you to some pretty advanced concepts which are going to tell us exactly when the Chamois Hagar’s geometry will outperform other gravel bikes, along with when it will fall short.

There is a lot of assumed knowledge in this article, so please make sure to start with the basics of frame geometry HERE.

What Is The Evil Chamois Hagar?

“Rather than start with a squirrely road bike and relaxing things into borderline manageable, we started with a mountain bike with shred surging through its veins and created the Chamois Hagar.”

– Evil Bikes

The lions share of Evil’s marketing is that the Chamois Hagar is a singletrack-capable gravel bike. With its unique frame geometry, Evil is signalling to you that when you buy their bike, you will not only speed along gravel roads, but you will be able to confidently tackle singletrack like you would on your mountain bike.

With 700c x 50mm tyre clearance, seven bidon cage mounts and a full-fender mounting kit, the bike is also marketed towards people interested in touring, bikepacking and commuting.

Long Reach, Short Stems

The first thing we need to understand about The Hagar is that it is following a gravel bike trend where manufacturers are increasing the ‘reach’ of their frames. These bikes have been designed to work specifically with short stems, which are necessary in order to maintain the same distance to the handlebars.

Longer top tubes are actually a great idea for gravel bikes as a longer overall wheelbase will provide more stability on rougher terrain, and the longer front centre provides extra toe clearance from the front wheel.

The downside to long reach gravel bikes is that they have a front-to-rear weight bias that reduces the front tyre grip in some situations.

Front and Rear Weight Distribution

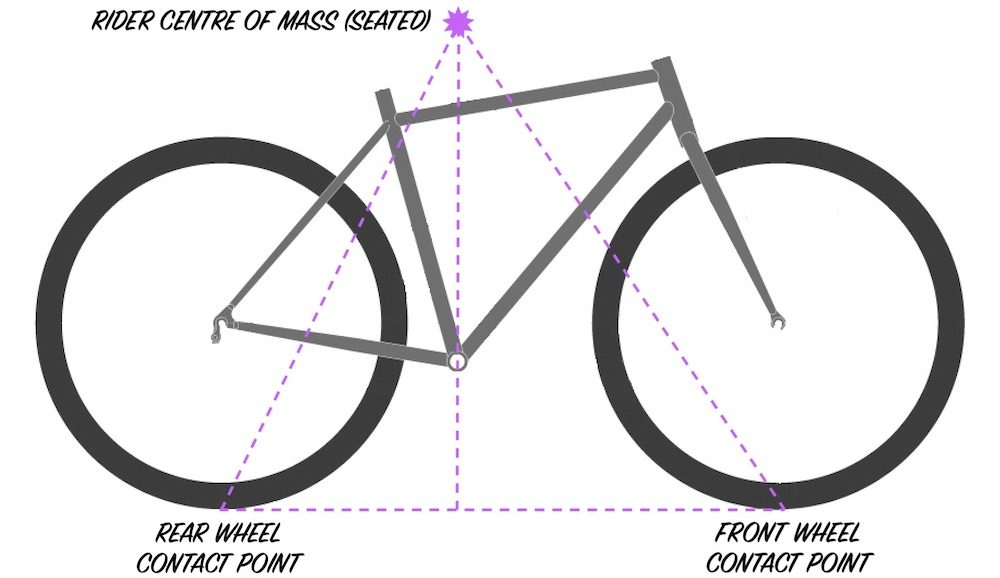

When we ride, a percentage of our body weight is distributed to the front and rear tyres. The typical rider has a centre of mass located around their hips when seated, which is almost exactly over the bottom bracket shell.

Sudden accelerations while riding tip us forwards, not backwards, so that’s why bicycles are almost always designed to put more weight on the rear tyre. If we make the front of a bike too short and steep, we allocate too much weight to the front wheel, making it easy to go over the handlebars on steep gradients. Conversely, when we have too little weight on the front wheel, the result is not enough front tyre grip when cornering (ie. understeering).

So how does the weight distribution of the Evil Chamois Hagar compare with a typical gravel bike?

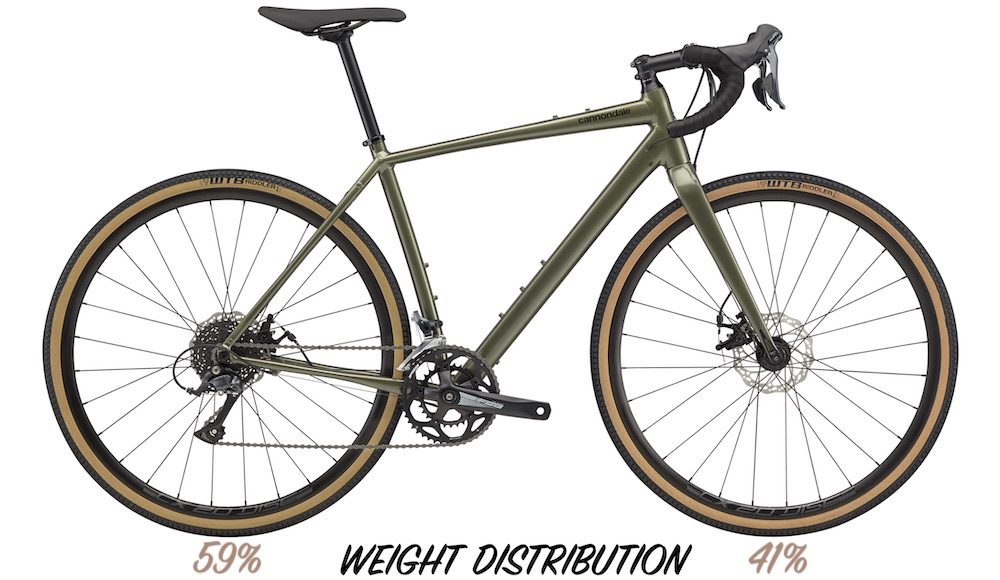

Weight Distribution: Cannondale Topstone

XS – 58.2% R, 41.8% F

S – 58.6% R, 41.4% F

M – 59.1% R, 40.9% F

L – 60.1% R, 39.9% F

XL – 60.8% R, 39.2% F

Average: 59.4% Rear Tyre, 40.6% Front Tyre

A pretty typical gravel bike is the Cannondale Topstone. When cycling on flat surfaces while seated, around 59% of your body weight will end up on the rear tyre and the other 41% on the front. Due to frame geometry constraints, shorter riders will have a bit more of their weight on the front wheel than taller riders.

And The Hagar?

Weight Distribution: Evil Chamois Hagar (Rider centre of mass adjusted in accordance with the varying seat tube angles and bottom bracket heights)

Small – 61.5% R, 38.5% F

Medium – 61.8% R, 38.2% F

Large – 61.7% R, 38.3% F

XLarge – 61.6% R, 38.4% F

Average: 61.7% Rear Tyre, 38.3% Front Tyre

When you ride seated, The Hagar will shift between 0.8% (size XL) and 3.3% (size S) of your body weight from the front tyre. This may not sound like a lot, but on flat corners, or on steep climbs, a couple of kilograms makes a big difference in terms of front grip. Yes, you can get some of this grip back by reducing the front tyre pressure, but ultimately, it’s the bodyweight on the front tyre that’s needed most.

Tall cyclists will find much less difference in front grip between The Hagar and a typical gravel bike. This is thanks to the steep 74.5-degree seat tube angle which helps to bring more bodyweight to the front tyre.

When standing up on the pedals, riders of all heights can expect The Hagar to offer similar levels of grip to a typical gravel bike. This is because, when standing, it’s much easier to shift your body weight to the front tyre.

Right, let’s look at a slightly different gravel bike design.

Weight Distribution: Rivendell Atlantis (Rider centre of mass adjusted in accordance with the varying seat tube angles and bottom bracket heights)

47 – 56.3% R, 43.7% F

50 – 56.6% R, 43.4% F

53 – 57.2% R, 42.8% F

55 – 57.5% R, 42.5% F

59 – 57.9% R, 42.1% F

62 – 58.4% R, 41.6% F

Average: 57.3% Rear Tyre, 42.7% Front Tyre

The Rivendell Atlantis has the longest rear centre (chainstays) of any gravel bike that I know of, ranging from 515mm through to 555mm. The result is a bike with a similar wheelbase to The Hagar, but instead of the wheelbase length being extended in front of the rider, it’s behind.

So how do long chainstays affect weight distribution?

The front tyre load on the Atlantis is substantially more in the small-sized bikes (5.2% more weight), but this reduces in the larger-sized bikes (3.2% more weight). You can expect an Atlantis to have a far superior front grip on flat and uphill terrain, but when the gradients pitch down, you will need to move your body weight behind your seat to get the equivalent front-to-rear grip balance of The Hager.

Weight Distribution and Bikepacking Bags

Ok, we’ve now established that, when seated, there is less front end grip on The Hagar compared to other bikes. The thing is, this is a bike travel website, so you better be out there carrying some gear!

Handlebar packs, cargo cage bags and stem bags will put weight back on the front tyre. The question is, how much extra weight on the fork and bars is needed to match the front tyre grip of a typical gravel bike? I’ve calculated it!

If you weigh:

60kg and ride a small Chamois Hagar, you will need ~2.0kg on the bars to match the front grip as a small Topstone.

80kg and ride a large Chamois Hagar, you will need ~1.3kg on the bars to match the front grip as a large Topstone.

100kg and ride an XL Chamois Hagar, you will need ~0.8kg on the bars to match the front grip as an XL Topstone.

The cool thing is that bikepacking bag setups usually distribute weight in front of a rider’s centre of mass – the seat pack is the only bag that sits behind. This means that, when fully kitted out with bikepacking bags, you can expect ample front tyre grip riding The Hagar.

Advantages Of A Long Front Centre

The Hagar may lose front grip in some situations, but for anything steep and fast, it will absolutely bomb.

This is for a few reasons:

1. The longer overall wheelbase helps to make a bike steadier at speed as it lowers your centre of mass.

2. When you stand up, your centre of mass is better centred between your tyres, maximising both front and rear tyre grip.

3. On steep downhill roads and trails, you don’t have to move your body as far back to centre your weight.

4. The Endo Angle is increased, which minimises how easy it is to go over the bars.

Wait, what’s the Endo Angle?

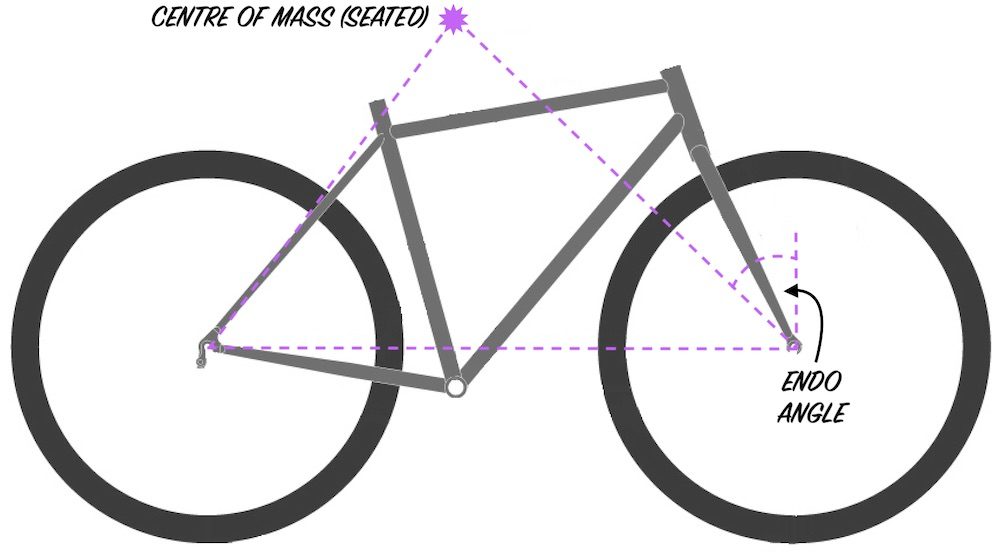

The Endo Angle

The Endo Angle determines how far you can pitch forward before hitting the tipping point.

When we increase the front centre of a bike, we get larger endo angles that reduce the ability to go over the bars on steep terrain. A larger endo angle essentially gives you more confidence when you’re heading downhill, especially after your front wheel hits a rock or some debris on the road. This is the number one factor that will make The Hagar a better singletrack descender than any other gravel bike available.

Evil Chamois Endo Angles (larger angles are better)

S – 44.5 degrees

M – 41.2 degrees

L – 38.3 degrees

XL – 36.0 degrees

Average: 40 degrees (10% more than typical gravel bikes)

Cannondale Topstone Endo Angles (larger angles are better)

XS – 40.3 degrees

S – 37.9 degrees

M – 35.9 degrees

L – 34.6 degrees

XL – 33.3 degrees

Average: 36.4 degrees

Rivendell Atlantis (larger angles are better)

47 – 42.1 degrees

50 – 40.5 degrees

53 – 39.5 degrees

55 – 38.7 degrees

59 – 37.8 degrees

62 – 36.9 degrees

Average: 39.3 degrees (very similar to The Hagar)

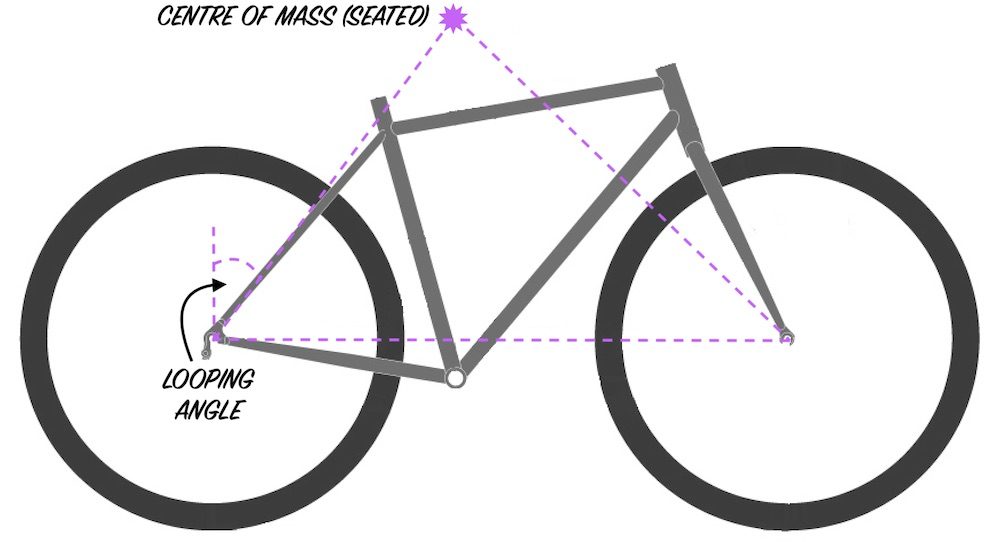

The Looping Angle

At the other end of the bike, the Looping Angle determines how far you can pitch backwards before hitting the tipping point.

More practically, a bike with a larger looping angle can ride up steeper terrain with more weight on the front tyre. There is actually not a huge difference between most gravel bikes of equal sizes as the chainstay lengths and seat tube angles are within quite a narrow range. There are two ways to get bigger looping angles on gravel bikes: we can move the rider’s centre of mass forward by steepening the seat tube angle, or we can fit longer chainstays to a bike.

As you can see below, the Evil’s steep seat tube angles allow the bike to climb up steeper terrain than typical. And the super long chainstays of the Rivendell allow it to climb much steeper terrain while having lots of weight on the front wheel.

Evil Chamois Looping Angles (larger angles are better):

S – 31.6 degrees

M – 28.5 degrees

L – 26.1 degrees

XL – 22.8 degrees

Average: 27.3 degrees (2% more than typical gravel bikes thanks to steep seat tube angles)

Cannondale Topstone Endo Angles (larger angles are better):

XS – 31.4 degrees

S – 28.8 degrees

M – 26.6 degrees

L – 24.6 degrees

XL – 22.9 degrees

Average: 26.9 degrees

Rivendell Atlantis (larger angles are better):

47 – 35.0 degrees

50 – 33.2 degrees

53 – 31.6 degrees

55 – 30.6 degrees

59 – 29.4 degrees

62 – 28.1 degrees

Average: 31.3 degrees (17% more than a typical gravel bike thanks to very long chainstays)

Chainstay Lengths

Shorter chainstays are usually preferred on both mountain and road bikes. They make a bike feel more nimble when making quick direction changes, for example, when riding on singletrack, or changing your position in a peloton. A particularly big advantage when cycling off-road is that short chainstays make your front wheel easier to lift over obstacles.

Long chainstays, on the other hand, have significant advantages for gravel bikes. Firstly, they lower the centre of mass, making gravel bikes more stable at speed. They also increase the looping angle, allowing you to cycle up steeper gradients with more weight on the front tyre.

Steering Speed

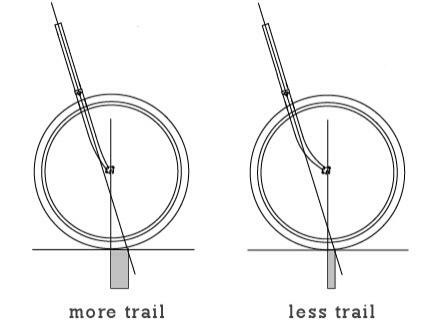

The product of the head tube angle and the fork rake/offset is the ‘trail’, and it’s the measurement that gives us the best indication of how fast a bike will steer.

Less trail equates to faster steering. This makes a bike more stable at low speeds because you can use the quick steering inputs to help you balance. However, at high speeds, these quick steering inputs work against you as they make your bike feel less stable.

More trail equates to slower steering. This makes a bike feel more stable at higher speeds because the steering inputs are less sensitive. At lower speeds, a high trail bike works out to be less stable because it has more wheel flop (more on this in the next section).

In essence, good bike design requires the balancing of steering agility with bike stability. Too slow steering makes a bike difficult to turn; too fast steering makes it unstable at speed.

The Evil Chamois Hagar is a high trail bike, so the steering is substantially slower than typical gravel bikes. But despite its ultra slack head tube angle, it’s not extreme by any means! In fact, there are two extremely popular bikepacking bikes that have similar steering speeds – the Salsa Cutthroat (87mm) and Salsa Fargo (92mm). With the slowing effect of the wider tyres (pneumatic trail), the Salsa bikes actually work out to steer slower in practice.

To increase its slow steering speed, The Hagar has been designed specifically around using a short stem. When we use smaller steering arcs, the handlebars become a touch more sensitive to steering inputs, which results in less effort required to change the direction of the bike.

That said, the best way to improve the handling of a slow steering bike – especially if you’re carrying any front luggage – is to increase the steering leverage. We can do this easily by installing a wider drop bar. Curve Bicycles specifically recommend their 600mm wide (brake hoods) Walmer drop bar with their new GMX bikepacking bike. If you want precise bike handling with bikepacking bags up front, a wide handlebar upgrade is going to be a must.

Wheel Flop

We’ve now determined that the steering is slow (but not totally unreasonable) on The Hagar, but there is one more aspect to its steering that is the biggest downside to a high trail bike – a large wheel flop.

This is the vertical distance the front axle lowers when the handlebars are turned (measured at 90 degrees). A bike with a large amount of wheel flop will, at low speeds (<20kph/12mph), constantly want to pull your bars to the side while you ride, requiring extra effort to keep the bike in a straight line.

With 60% more wheel flop than a typical gravel bike, The Hagar will undoubtedly be a bit of a handful on slow climbs. Then again, the Salsa Cutthroat and Fargo both have 50% more wheel flop than typical, and by most reports, they handle slow speeds just fine.

The good news is that wider handlebars are the antidote to not only the slow steering speed of The Hagar, but they’ll also reduce the effect of the wheel flop thanks to the additional steering leverage.

Progressive Geometry Summary: Evil Chamois Hagar

On balance, the Evil Chamois Hagar is actually NOT as wacky as it looks.

The front-to-rear weight distribution has been optimised for descending, so the bike will be incredibly stable at high speeds, handling steep backroad descents better than any other gravel bike available. On flat corners or steep climbs, this bike will require more work to maintain front tyre grip – in other words, you’ll need to shift more of your weight forward to get the equivalent grip. That said, when we factor in any luggage over the front wheel, you can expect no shortage of front end grip.

The long front centre, slack head tube angle and long fork rake results in an endo angle that is significantly larger than most gravel bikes. This reduces the feeling of going over the handlebars, allowing you to ride more confidently on singletrack, especially when things get rough and/or steep. Meanwhile, the looping angle up back is in line with other gravel bikes.

The steering of The Hagar is very slow compared to a typical gravel bike. At low speeds, you can expect the handlebars to pull to the sides thanks to the high wheel flop, and this will be compounded with any front luggage. The short stem of the Chamois Hagar speeds the steering up a touch, but ultimately, a wide handlebar with additional steering leverage is the best antidote to a high trail, high wheel flop bike.

How Could We Improve The Frame Geometry?

I know I’m jumping the gun here given I haven’t even ridden The Hagar… but based on the fundamentals of bike handling, there are a few ways we can improve the steering and weight balance of this bike, while still retaining the same downhill shred-ability – in theory at least.

1. More fork offset and less head tube angle. By tweaking these two values we can achieve a similarly long front centre and similarly big endo angle, but with quicker steering and less wheel flop (eg. 68 degrees + 60mm offset = 14% faster steering / 17% less wheel flop). Check out the Stooge MK4 or Jones Plus LWB to see this in practice.

2. Longer chainstays on the bigger frame sizes. By increasing the chainstay length and therefore looping angles, we can climb steeper gradients with more grip on the front wheel.

3. Steeper seat tube angles on the smaller frame sizes. This would put more weight on the front wheel, increasing the front tyre grip when cornering seated.

4. Shorter reach on the smaller frame sizes. Along with the steeper seat tube angles, we could decrease the frame reach, which would allow a much better fit of the wider handlebars necessary to offset the slow steering speeds.

Want An Evil Chamois Hagar For 25% of the Cost?

If you like the sound of The Hagar but not the cost (US $4799+), I’ll let you in on a little secret – you can build a gravel bike with a similar-ish geometry, for a fraction of the cost. Actually, I’d argue this rig would handle even better for most bikepacking speeds and terrain, especially with luggage on the front.

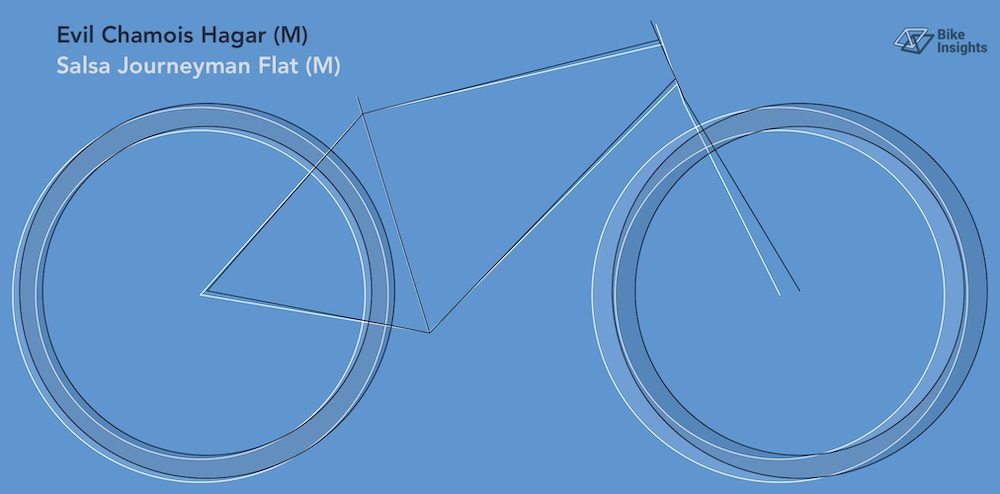

As you can see in the drawings, the Salsa Journeyman flat bar has a very similar overall geometry to The Hagar. At US $949, you could get the bike, install a Curve Walmer or Ritchey Venturemax XL handlebar and shorter stem for $170, then fit up some Claris shifters for another $100, and ta-da – a budget bike, not all that dissimilar to the Evil Chamois Hagar… for quite literally 25% of the cost.

What’s Next?

I love that the Evil Chamois Hagar offers something a little different to the norm, which gives us pause for thought about what actually constitutes a good frame geometry for gravel bikes.

In the next few years, you can expect to see many more gravel bikes with a longer frame reach and shorter stems. I can’t imagine you’ll see a 66-degree head tube angle on another gravel bike (I might have to swallow those words), but off-road specific gravel bikes will likely settle on 68 or 69-degree head tube angles paired with longer fork rakes.

Head HERE To See Six Other Bikepacking Bike Trends For 2020